The Coalition for Hemophilia B (English)

Haemophilia is a hereditary, congenital condition in which there is a shortage of clotting factors in the blood. As a result, the blood does not clot properly and will result in regular haemorrhages. People with haemophilia bleed faster in comparison to healthy people and if they have an injury, the blood loss will last longer. Haemophilia is also called bleeder's disease.

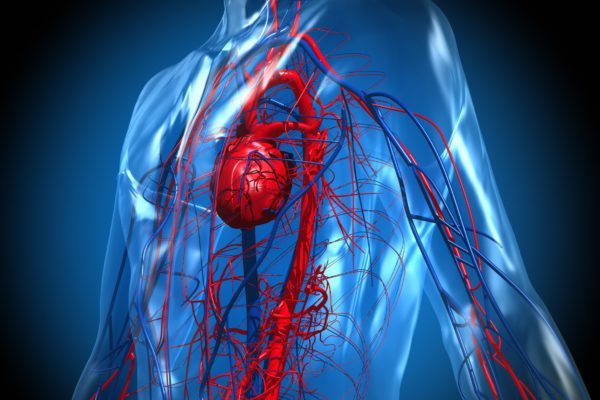

Platelets and coagulation factors normally ensure that a wound is quickly closed and does not continue to bleed. Platelets move to the location of the damaged blood vessels and attach to each other to form a closing clot. At the same time, clotting factors cause the production of fibrin threads: a filamentous, insoluble protein to which blood cells stick. This forms the final clot. After the damage has healed, the body breaks down the clots.

In patients with haemophilia, a certain coagulation factor is not produced. Depending on the type of the (partially) missing coagulation factor, haemophilia A (coagulation factor VIII) or haemophilia B (coagulation factor IX) is diagnosed. The severity of haemophilia can vary from severe to moderate to mild. This is determined by the amount of factor VIII or IX present in the blood.

An estimated 400,000 people worldwide have haemophilia. The Netherlands has around 1,600 patients, which means that about 1 in 10,000 people have haemophilia. Haemophilia A accounts for approximately 85% of cases, whilst 15% have haemophilia B. It is a sex-linked inherited disorder carried on the X chromosome, and mainly diagnosed in men as a result.

The symptoms presented by the patient depend on the severity of the haemophilia. The main symptoms are haemorrhage, mainly at the muscles and joints. These arise spontaneously or after minor injuries. Due to the lack of coagulation factor VIII or IX, patients with haemophilia bleed more often and for longer. In small children, bruises and small haemorrhages are often the first signs of haemophilia and often start when they start to crawl and walk.

The symptoms of haemophilia A are similar to those of haemophilia B. Symptoms are:

• Large bruises.

• Spontaneous haemorrhages.

• Prolonged blood loss after dental visits, injuries or operations.

• Internal haemorrhages in muscles and joints.

• Increased risk of serious internal bleedings after serious accident.

• stroke.

After a seemingly mild injury, haemophiliacs can get internal bleedings with serious consequences. Haemorrhages in the muscles and joints can cause permanent damage resulting in osteoarthritis. When it occurs in a vital organ such as the brain, the situation becomes life threatening.

The cause of haemophilia is a deficiency, or the lack of, a clotting factor in the blood. Patients with haemophilia lacs (a part of) coagulation factor VIII and people with haemophilia B lack coagulation factor IX. The haemophilia gene is located on the X chromosome and therefore haemophilia is a sex-linked hereditary condition. Because of the fact that men have only one X chromosome, they have a higher chance on haemophilia in comparison with women. Women need two defective genes (one from the father as well as the mother) and therefore are often only carriers.

In most cases, patients with haemophilia already have family members with the disease. However, in about 30% of the patients there is no one in the family with the illness. In this group, the disease is caused by a spontaneous mutation in the factor VIII or IX genes of the mother.

Because haemophilia is a rare disease, it is not easily recognised by the medical professional. If the doctor suspects that the patient has haemophilia, it is possible to measure the amount of clotting factor in the blood. If the activity of coagulation factor VIII or IX is reduced or not present at all, they may conclude that the patient has haemophilia.

The diagnosis is made by:

• Careful registration of complaints and symptoms through a structured medical history. Attention is paid to haemorrhages that occur immediately after birth, in the joints and muscles, after surgery and dental interventions. The medical professional also takes the coagulation disorders in the family into account.

• Physical examination.

• Blood test: test the level of factor VIII or factor IX activity.

• Prenatal diagnosis by means of a chorionic test at 9-11 weeks of pregnancy when the mother is a known carrier of the disease. Accurate determination of sex can also be performed by taking blood from the mother by means of Y-PCR. In the case of a girl, further investigations can be omitted.

There is still no curative treatment for this disease, but is relatively easy to treat. Bleeding can be prevented and treated by the administration of coagulation factor VIII in haemophilia A and coagulation factor IX in haemophilia B patients. Depending on the severity of the disease, patients may need to be given coagulations factors up to 3 times a week and for life. The missing coagulation factor is administered intravenously (via a vein) and ensures temporarily that there is sufficient clotting factor in the blood to be able create a clot if there is a bleed.

In the past, these clotting factors were removed from the blood of donors. Nowadays, the required substances are prepared from cultured cells. These are known as recombinant clotting factors. The majority of patients are treated preventatively with coagulation factors to prevent bleeding (prophylaxis).

A lot of ongoing research is focussed on new types of treatment, such as gene therapy. With this type of therapy, a new gene is introduced into the body that takes care of the production of clotting factors. Recent research among 10 patients with severe haemophilia B showed that gene therapy can be used safely and effectively. This means that patients do not have to be injected with coagulation agents 2 to 3 times per week.